悦读|露易丝·格丽克:2020年诺贝尔文学奖获奖感言(双语)

原标题:悦读|露易丝·格丽克:2020年诺贝尔文学奖获奖感言(双语)

悦读|露易丝·格丽克:2020年诺贝尔文学奖获奖感言(双语)

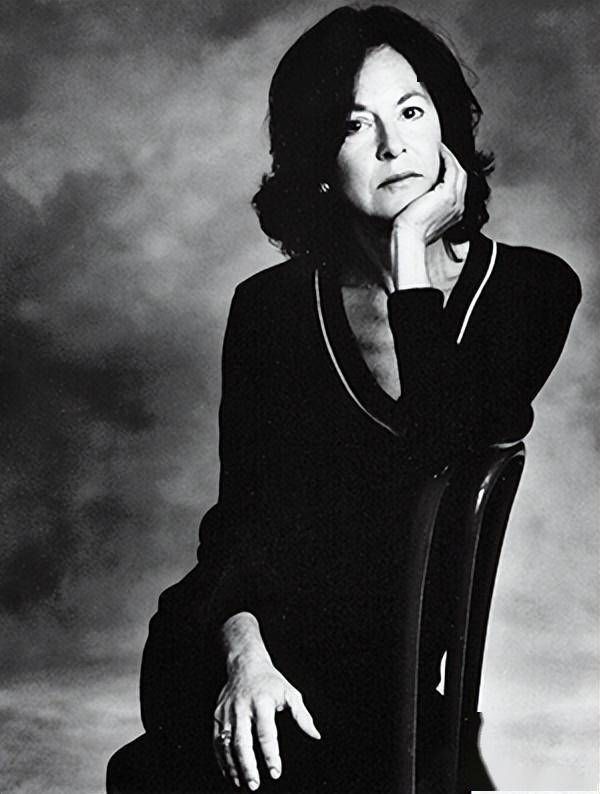

(图源:诺奖官网)

美国当地时间2023年10月13日,诺贝尔文学奖得主、美国前桂冠诗人露易丝·格丽克(Louise Glück,1943—2023)在马萨诸塞州剑桥市的家中去世,享年80岁。她优雅、敏锐而又热烈的生命,从此去往彼岸的世界,如她所写的珀耳塞福涅在秋天回到冥界。

露易丝·格丽克1943年4月22日生于纽约长岛一个匈牙利裔犹太人家庭,生前已出版十四部单行本诗集、两部随笔集和一部小说,曾获得包括普利策奖、美国国家图书奖、全国书评界奖、美国诗人学院华莱士·斯蒂文斯奖、波林根奖等各类奖项。2020年,格丽克获得诺贝尔文学奖,评委会给出的理由是,“她那具有朴素之美的、精确的诗意声音,令个体的存在获得了普遍性”。(The Nobel Prize in Literature 2020 was awarded to Louise Glück "for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal".)

格丽克的写作深受希腊神话等古典资源的影响,也常常从对大自然的观察中获得启示。她曾经历过两次婚姻并离婚。爱与丧失成为她诗歌的重要主题。她常常写到自己早夭的姐姐、自己的亲人以及与亲密之人充满紧张和失落感的关系。本刊2020年第11期曾选刊其诗作《夜徙》(The Night Migrations)。

今天为大家推荐格丽克在获得诺贝尔奖后发表的获奖感言,可以看出,即便是在领奖这样的重大时刻,诗人依然保持着冷静和对诗歌的虔诚。就让我们在阅读中纪念这位诗人,她曾给我们带来无可比拟的美。

Nobel Lecture

诺贝尔奖获奖感言

By Louise Glück

译/李琬

审校/柳向阳 陈欢欢

When I was a small child of, I think, about five or six, I staged a competition in my head, a contest to decide the greatest poem in the world. There were two finalists: Blake’s “The Little Black Boy” and Stephen Foster’s “Swanee River.” I paced up and down the second bedroom in my grandmother’s house in Cedarhurst, a village on the south shore of Long Island, reciting, in my head as I preferred, not from my mouth, Blake’s unforgettable poem, and singing, also in my head, the haunting, desolate Foster song. How I came to have read Blake is a mystery. I think there were a few poetry anthologies in my parents’ house among the more common books on politics and history and the many novels. But I associate Blake with my grandmother’s house. My grandmother was not a bookish woman. But there was Blake, The Songs of Innocence and of Experience, and also a tiny book of the songs from Shakespeare’s plays, many of which I memorized. I particularly loved the song from Cymbeline, understanding probably not a word but hearing the tone, the cadences, the ringing imperatives, thrilling to a very timid, fearful child. “And renownèd be thy grave.” I hoped so.

当我还是个小孩子的时候,大概是五六岁吧,我的脑子里上演着一场竞赛,一场能够选出世界上最伟大诗作的比赛。有两首诗进入了决选名单:威廉·布莱克的《小黑孩》和斯蒂芬·福斯特的《斯旺尼河》。我祖母的房子坐落于纽约长岛南岸的西达赫斯特村,当时我就在那座房子的次卧里来回踱步,像我习惯的那样,在脑中默默地而非出声地背诵布莱克那令人难忘的诗,同样,也在脑中默默地哼唱福斯特的那首沉痛、凄凉的歌。我为什么会读到布莱克还是个谜。我想在我父母家,除了更加常见的有关政治、历史的书和大量的小说,还有少量诗集。但我总是把布莱克和祖母家联系起来。我的祖母不是个好读书的女人,但她那儿有布莱克《天真与经验之歌》,还有一本小书,汇编了从莎士比亚戏剧中选出的歌词——有不少我都能背诵。我格外喜欢《辛白林》中的歌,或许当时一个字也不懂,却能清楚地听到那语调、格律、铿锵的祈使句,这令一个胆怯恐惧的孩童格外兴奋。“墓草长新,永留记忆。”我也希望如此。

Competitions of this sort, for honor, for high reward, seemed natural to me; the myths that were my first reading were filled with them. The greatest poem in the world seemed to me, even when I was very young, the highest of high honors. This was also the way my sister and I were being raised, to save France (Joan of Arc), to discover radium (Marie Curie). Later I began to understand the dangers and limitations of hierarchical thinking, but in my childhood it seemed important to confer a prize. One person would stand at the top of the mountain, visible from far away, the only thing of interest on the mountain. The person a little below was invisible.

这类为了荣耀和至高奖赏而开展的比赛,对我来说是十分自然的事;我启蒙时期最早读过的神话里充满了这类比赛。即使在我很小的时候,在我看来,世上最伟大的诗就是高级荣誉中最高级的那种。这也是父母培育我和我妹妹的方式,我们要去拯救法国(圣女贞德),要去发现镭元素(玛丽·居里)。后来,我开始认识到这种等级制思维中的危险和局限性,但对于幼年的我来说,发奖这件事却非常重要。会有一个人站在山巅,从很远处就能看见,那是山上唯一引人注意的东西。站在下面一点点的人就看不见了。

Or, in this case, poem. I felt sure that Blake especially was somehow aware of this event, intent on its outcome. I understood he was dead, but I felt he was still alive, since I could hear his voice speaking to me, disguised, but his voice. Speaking, I felt, only to me or especially to me. I felt singled out, privileged; I felt also that it was Blake to whom I aspired to speak, to whom, along with Shakespeare, I was already speaking.

或者,我说的人在这里也可以换成诗。那时我非常确信,不知为何,布莱克一定知道我脑子里的这场比赛,而且对结果十分关心。我知道他已经死了,但我觉得他还活着,我能听到他对我说话的声音,被伪装起来了,但依然就是他的声音。我感到他只在对我说话,或是专门对我说话。我感到自己被选中,非常幸运;我也感到,我格外渴望和布莱克说话,而和莎士比亚一道,他已经成为我交谈的对象。

Blake was the winner of the competition. But I realized later how similar these two lyrics were; I was drawn, then as now, to the solitary human voice, raised in lament or longing. And the poets I returned to as I grew older were the poets in whose work I played, as the elected listener, a crucial role. Intimate, seductive, often furtive or clandestine. Not stadium poets. Not poets talking to themselves.

布莱克获胜了。但后来我意识到那两首诗多么相似;那时和现在一样,我都被那出于哀伤或渴望的孤独的人类声音所吸引。随着我长大,我不断重读一些诗人,而在他们的诗中,我自己曾作为被选中的聆听者,扮演了重要角色。亲密的,诱惑的,往往是幽暗的、秘密的。不是那些站在露天竞技场上的诗人。不是那些自说自话的人。

I liked this pact, I liked the sense that what the poem spoke was essential and also private, the message received by the priest or the analyst.

我喜欢这种协定,我喜欢这种感觉:一首诗说出的东西不仅必要,而且私密,它们是神父或心理医生会聆听的话语。

The prize ceremony in my grandmother’s second bedroom seemed, by virtue of its secrecy, an extension of the intense relation the poem had created: an extension, not a violation.

我祖母家的次卧里进行的授奖仪式,因其秘密性,仿佛就是一首诗所创造的那种强大关联感的延伸:一种延伸,而不是违背。

Blake was speaking to me through the little black boy; he was the hidden origin of that voice. He could not be seen, just as the little black boy was not seen, or was seen inaccurately, by the unperceptive and disdainful white boy. But I knew that what he said was true, that his provisional mortal body contained a soul of luminous purity; I knew this because what the black child says, his account of his feelings and his experience, contains no blame, no wish to revenge himself, only the belief that, in the perfect world he has been promised after death, he will be recognized for what he is, and in a surfeit of joy protect the more fragile white child from the sudden surfeit of light. That this is not a realistic hope, that it ignores the real, makes the poem heartbreaking and also deeply political. The hurt and righteous anger the little black boy cannot allow himself to feel, that his mother tries to shield him from, is felt by the reader or listener. Even when that reader is a child.

布莱克通过那个黑人小男孩对我说话;他是那个声音的隐秘源头。他隐而不见,正如那个黑人小男孩在那个漠然、轻蔑的白人男孩那里也是看不见的,或者看不真切的。但我知道他说的是真的,在他那暂时性的、必死的身躯之中包含着他闪闪发光的纯洁灵魂;我知道这一点,因为那个黑人小孩所说的,他对体验和经验的描述,不带有任何指责,也没有想要为自己复仇,只是传递着这样的信念:在那个他死后将要去的完美世界,人们会按照他真正的本质认识他,而他会带着莫大的喜悦保护那个更脆弱的白人小孩,防止他被过多的阳光晒伤。这个信念不是一种现实的期望,它忽略了现实,让这首诗令人心碎,同时也为它赋予了深刻的政治性。黑人小男孩不允许自己体验的伤害和正当的愤怒,他的母亲希望为他遮挡的伤害和愤怒,却被读者或听者体验到了。即使那个读者也还只是个孩子。

But public honor is another matter.

但公共的荣誉是另一回事。

The poems to which I have, all my life, been most ardently drawn are poems of the kind I have described, poems of intimate selection or collusion, poems to which the listener or reader makes an essential contribution, as recipient of a confidence or an outcry, sometimes as co-conspirator. “I’m nobody,” Dickinson says. “Are you nobody, too? / Then there’s a pair of us — don’t tell…” Or Eliot: “Let us go then, you and I, / When the evening is spread out against the sky / Like a patient etherised upon a table…” Eliot is not summoning the boyscout troop. He is asking something of the reader. As opposed, say, to Shakespeare’s “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day”: Shakespeare is not comparing me to a summer’s day. I am being allowed to overhear dazzling virtuosity, but the poem does not require my presence.

那些我毕生都狂热迷恋的诗是我之前描述的那种诗,是包含了私人的的选择、密谋的诗,那些诗包含了读者或听者的重要贡献,他们倾听着诗中的一个秘密或一声怒吼,而且有时也参与了共谋。“我是无名之辈,”艾米丽·狄金森说,“你也是无名之辈吗?/那我们就是一对了——别声张……”或者艾略特:“那么我们走吧,你我两个人,/正当朝天空慢慢铺展着黄昏,/好似病人麻醉在手术桌上……”艾略特不是在召集童子军队列。他在向读者发言。与之相反的是莎士比亚的“我能否将你比作夏日”:莎士比亚并不是把我比作夏日。我在这首诗中,有幸偷听了炫目的精妙乐音,但这首诗并不要求我在场。

In art of the kind to which I was drawn, the voice or judgment of the collective is dangerous. The precariousness of intimate speech adds to its power and the power of the reader, through whose agency the voice is encouraged in its urgent plea or confidence.

在吸引我的那类艺术中,由集体发出的声音或裁决是危险的。亲密言词的不确定性增强了这种言词的力量和读者的力量,而正是读者的存在,鼓励着这种声音表达急迫恳求或倾诉秘密。

What happens to a poet of this type when the collective, instead of apparently exiling or ignoring him or her, applauds and elevates? I would say such a poet would feel threatened, outmaneuvered.

当一个集体开始对这类诗人鼓掌、颁奖,而不是在放逐和无视他/她,这样的诗人会遭遇什么呢?要我说,这个诗人会觉得受到威胁和操控。

This is Dickinson’s subject. Not always, but often.

这是狄金森的主题。并非全是,但常常是。

I read Emily Dickinson most passionately when I was in my teens. Usually late at night, post-bedtime, on the living room sofa.

在我十几岁时,我读艾米丽·狄金森最有热情。通常是在深夜,在上床时间之后,在客厅沙发上。

I’m nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

我是无名之辈!你是谁?

你也是无名之辈吗?

And, in the version I read then and still prefer:

还有我当时读的也至今更喜欢的那个版本写道:

Then there’s a pair of us — don’t tell!

They’d banish us, you know…

那我们就是一对了——别声张!

他们会把我们赶走,你知道……

Dickinson had chosen me, or recognized me, as I sat there on the sofa. We were an elite, companions in invisibility, a fact known only to us, which each corroborated for the other. In the world, we were nobody.

当我坐在沙发上,狄金森选中了我或者认出了我。我们惺惺相惜,在不可见处相互陪伴,这是仅有我们知晓的事实,而我们的观点在彼此那里得到确证。而在这世界上,我们是无名之辈。

But what would constitute banishment to people existing as we did, in our safe place under the log? Banishment is when the log is moved.

但对我们这样生存的人,安居于原木下面自己的安全地带的人来说,什么会构成一种驱逐?驱逐就是当木头被移开的时候。

I am not talking here about the pernicious influence of Emily Dickinson on teenaged girls. I am talking about a temperament that distrusts public life or sees it as the realm in which generalization obliterates precision, and partial truth replaces candor and charged disclosure. By way of illustration: suppose the voice of the conspirator, Dickinson’s voice, is replaced by the voice of the tribunal. “We’re nobody, who are you?” That message becomes suddenly sinister.

在此我谈论的不是艾米丽·狄金森对青春期少女的恶劣影响。我谈论的是一种性格,这种性格不信任公共生活,或者认为公共生活领域就意味着概括会抹去精确,片面的真相会取代坦率的、充满感性的揭露。举个例子:假设这密谋者的声音,狄金森的声音,被特别法庭的声音所取代。“我们是无名之辈,你是谁?”这种断言一瞬间就变得险恶了。

It was a surprise to me on the morning of October 8th to feel the sort of panic I have been describing. The light was too bright. The scale too vast.

10月8日早上,我惊讶地感受到刚刚描述的这种惊慌。光线太明亮了。声势也太浩大了。

Those of us who write books presumably wish to reach many. But some poets do not see reaching many in spatial terms, as in the filled auditorium. They see reaching many temporally, sequentially, many over time, into the future, but in some profound way these readers always come singly, one by one.

我们这些作家大概都渴望拥有许多读者。然而,有些诗人不会追求在空间意义上抵达众多读者,如同坐满的观众席那样。他们设想中的拥有众多读者是指时间意义上的,是渐次发生的,许多读者在时间流逝中到来,在未来出现,但这些读者总是以某种深刻的方式,单独地到来,一个接一个地出现。

I believe that in awarding me this prize, the Swedish Academy is choosing to honor the intimate, private voice, which public utterance can sometimes augment or extend, but never replace.

我相信,瑞典学院把这个奖颁给我,是想要奖励那种亲密的、私人的声音,公开表达可能有时会增强、扩展这种声音,但绝不会取代它。

【附诗·两首】

The Little Black Boy

小黑孩

By William Blake

译/杨苡

My mother bore me in the southern wild,

And I am black, but O! my soul is white;

White as an angel is the English child,

But I am black, as if bereav’d of light.

在南方的荒野我妈把我生养,

我是黑的,但是啊!我的灵魂却洁白,

英国的孩子洁白得像天使一样,

可我是黑的,像是被掠夺去光彩。

My mother taught me underneath a tree,

And sitting down before the heat of day,

She took me on her lap and kissed me,

And pointing to the east, began to say:

在一棵树下我妈教导着我,

坐下来,白昼尚未炎热,

她把我抱上膝头亲吻着我,

用手指着东方,开始对我说。

“Look on the rising sun: there God does live,

“And gives his light, and gives his heat away;

“And flowers and trees and beasts and men receive

“Comfort in morning, joy in the noonday.

看那升起的太阳:上帝就在那里居住,

放射着他的光,散发着他的热。

人和兽,花朵和树木

接受着黎明的舒畅,中午的欢悦。

“And we are put on earth a little space,

“That we may learn to bear the beams of love;

“And these black bodies and this sunburnt face

“Is but a cloud, and like a shady grove.

把我们安置在地上一点点空间,

让我们学着承受一点爱的光线。

这黑黑的躯体和这被太阳晒焦的脸,

不过是一朵乌云,像荫蔽的丛林一片。

“For when our souls have learn’d the heat to bear,

“The cloud will vanish; we shall hear his voice,

“Saying: ‘Come out from the grove, my love & care,

“‘And round my golden tent like lambs rejoice.’”

因为等到我们的灵魂学会忍受酷热,

乌云便将消逝,我们将听见他的声音,

说:走出丛林,我的爱,我的宝贝,

像欢腾的羔羊般地围着我金色的帐篷。

Thus did my mother say, and kissed me;

And thus I say to little English boy:

When I from black and he from white cloud free,

And round the tent of God like lambs we joy,

我母亲就这样讲了,还亲吻了我。

我就对小英国孩子也这样讲。

当我脱离了乌云,他离了白云,

我们就围着上帝的帐篷欢腾如羔羊。

I’ll shade him from the heat, till he can bear

To lean in joy upon our father’s knee;

And then I’ll stand and stroke his silver hair,

And be like him, and he will then love me.

我将给他遮阳直到他能忍受酷热,

高兴地倚靠在我们天父的膝前,

那时我将站起来将他的银发抚摸,

我将像他一样,他也将对我眷恋。

☆ ★ ☆ ★ ☆ ★

“I’m nobody! Who are you?”

“我是无名之辈!你是谁?”

By Emily Dickinson

译/李琬

I’m nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there’s a pair of us — don’t tell!

They’d banish us, you know.

我是无名之辈!你是谁?

你也是无名之辈吗?

那我们就是一对了——别声张!

他们会把我们赶走,你知道。

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!

成为有名人物,多么可怕!

多么乏味啊,像只青蛙,

整日把你的名字

向那仰慕你的泥沼念诵!

英文来源:诺奖官网

中文及图片来源:世纪文景

责任编辑:

相关知识

诺贝尔文学奖得主露易丝·格丽克逝世,终年80岁

2020年诺贝尔文学奖得主露易丝·格丽克逝世,享年八十岁

诺贝尔文学奖得主、诗人露易丝·格丽克逝世,享年80岁

诺贝尔文学奖得主露易丝·格丽克逝世:她的诗歌是要创造一个世界

诺贝尔文学奖得主露易丝·格丽克逝世:她的诗歌不是一棵树,而是衍生出一片丛林

纪念丨露易丝·格丽克诺奖演讲全文

2023年诺贝尔文学奖揭晓!挪威作家约恩•福瑟获奖,中国作家残雪遗憾落榜

2023诺贝尔文学奖获得者,是他!

刚刚,2023年诺贝尔文学奖揭晓!

诺贝尔文学奖得主路易丝·格吕克去世

推荐资讯

- 1李沁肖战已同居领证? 李沁肖 49331

- 2闫妮老公邹伟平简历 闫妮前 44838

- 3王凯蒋欣承认已有一子? 结 40923

- 4王灿前夫 王灿的第一任老公 36688

- 5汪希玥回北京过年,怎料见到汪 32795

- 6霍启山与霍启仁对嫂子郭晶晶的 29810

- 7张佳宁和宋轶长得像 同属甜美 25864

- 8央视主持孙小梅丈夫曝光,是大 21288

- 960年代,洪秀柱(右后)与父 20225

- 10佟丽娅事件是什么 佟丽娅回应 19582